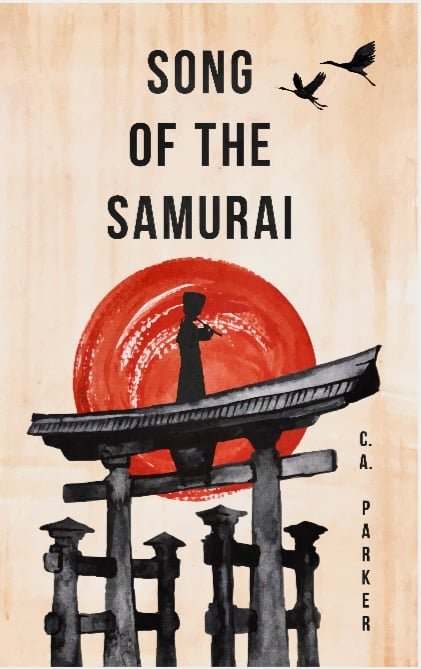

Song of the Samurai

Japan 1745 is a land under the iron grip of the Tokugawa shoguns. Roads are monitored, dissent stifled, and order maintained through blackmail and an extensive network of informers. Amid rumors of rebellion, Kurosawa Kinko–samurai and monk–is expelled in disgrace as the head music instructor of his Zen temple in Nagasaki. He begins an odyssey across Japan, dogged by agents and assassins from an unknown foe. Along his journey, Kinko encounters a compelling cast of merchants, ronin, courtesans, spies, warriors, hermits, and spirits, on a quest to redeem his honor. Inspired by the life of the historical Kurosawa Kinko (1710-1771), master of the shakuhachi flute and founder of the Kinko-ryu school, Song of the Samurai takes the reader on a richly-textured exploration of feudal Japan and the complexities of the human spirit.

Song of the Samurai

Inspired by the true story of shakuhachi master Kurosawa Kinko, a lone samurai monk journeys across Edo period Japan, encountering merchants, rōnin, courtesans, spies, warriors, hermits, and spirits on a quest to redeem his honor.

Pre-order song of the samurai here:

Produced by Jeremy Marquez at idesignnyc (www.idesignnyc.com)

The Shakuhachi

The shakuhachi is a vertical, end-blown bamboo flute, roughly 21 inches in length. It has five holes (four on the front and one on the back) and naturally plays a minor pentatonic scale, although any note can be played by partially covering the holes and by raising or lowering the chin. The name of the instrument derives from its standard length: one shaku (a Japanese measurement of roughly a foot), and eight sun (one-tenth of a shaku); thus i-shaku-hachi-sun. Although this length (in which the base note is a D) is standard, the flutes are made in a variety of lengths from only a foot to over three feet, each playing in different musical keys. The term “shakuhachi” is currently used, regardless of the length.

Arriving in Japan from China (perhaps through Korea) in the 7th-8th century, the shakuhachi was originally used in court ensemble music (gagaku in Japanese) for roughly two centuries. After disappearing for several centuries, the flute re-emerged in the 15th-16th century in the hands of a group of mendicant monks called komosō or “straw mat monks,” so named for the sleeping mats that they carried on their backs. This sect morphed into a group called the komusō or “monks of nothingness.”

The Fuke

The komusō called their order the Fuke-shu (named after an ancient Chinese monk) and associated themselves with the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. Like other Rinzai monks, they practiced zazen or sitting meditation, but they also blew the shakuhachi as a form of meditation called sui zen or “blowing meditation.”

Fuke temples appeared around the country during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, each developing their own musical pieces used for meditation. Most temples also practiced some version of the three oldest musical pieces: Koku (Empty Sky), Kyorei (Hollow Bell), and Mukaiji (Flute on a Misty Sea). In the mid-18th century, the central temple in Edo (modern Tokyo) commissioned its head instructor, Kurosawa Kinko to visit temples all over the country to collect the music that each temple played. Kinko’s collection of 36 pieces became the core of the Kinko-ryu school of shakuhachi playing that still exists today.

Kurosawa Kinko

Kinko Kurosawa (1710-1771) was born in the Kuroda region of Kyushu, on the north side of the island. He became a member of the Fuke Temple of Kuzaki-ji in Nagasaki where he learned to play the shakuhachi under the tutelage of an instructor named Ikkei. He traveled extensively, under the commission of Ichigetsu-ji Temple in Edo, collecting honkyoku – literally “original music” – from Fuke temples all over Japan. These 36 pieces became the core repertoire of the Kinko-ryu shakuhachi school.

Relatively little is known of the historical figure of Kurosawa Kinko. His actual diaries were destroyed in an air raid on Tokyo in 1944. Many historical texts refer to him as a Fuke monk. However, many scholarly papers have noted that – at least by the end of his life – he appears to have been a layperson, although commissioned to teach at the largest Fuke temple of Ichigetsu-ji. This novel uses that nearly-blank canvas to paint a picture inspired by this remarkable life. While all of the characters in the novel, besides Kurosawa himself and his teacher Ikkei, are fictitious, all of the places in the novel are (or were) actual places, many of which we know that he visited.